What is Anxiety?

Anxiety is the body and mind’s natural reaction to threat or danger. Commonly referred to as the ‘fight or flight’ response, the body releases hormones such as adrenaline, which in turn results in a number of physiological reactions occurring in the body. These emotions help us to survive by ensuring that we are alert and responsive to danger.

In the appropriate situation, high levels of anxiety – even panic – is considered normal and helpful if it prompts us to escape from danger. Anxiety in performance situations such as interviews and exams can help us perform to the best of our ability. The problems arise when people’s response (anxiety) is out of proportion to the actual danger of the situation, or that it is generated when there is no danger present.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anxiety is something we all experience from time to time. However, when anxiety becomes excessive or debilitating then it is considered an anxiety disorder. Over the last few decades, there has been a dramatic improvement in our understanding of anxiety and how it can be treated.

Along with depression, anxiety disorders are the most common mental health problem affecting the population of Ireland and Europe. The main symptoms of anxiety disorder is excessive worry or fear, this can feel overwhelming and debilitating and can have a significant impact on an individual’s everyday life.

Some individuals will seek and receive appropriate treatment which can significantly improve their ability to manage and cope. There is no accurate data in Ireland in relation to the prevalence of anxiety disorder.

Anxiety disorders are not age-specific. The age of onset is quite variable, ranging from childhood and adolescence to adulthood. Frequently, anxiety disorders are associated with other anxiety disorders, for example agoraphobia combined with panic disorder. There is also the association between anxiety disorders and other disorders, such as depression, substance/alcohol misuse.

Some researchers suggest that primary anxiety disorders are thought to result from a combination of a genetic predisposition, environmental factors and life stress. It can occur as a result of exposure to a negative life event for a child/adult or a history of anxiety in biological relatives.

Physiological reactions in the brain and body, distorted thoughts and beliefs about risk and danger and patterns of behaviour, such as avoidance or safety seeking, all interact to develop and maintain the problem.

Features of anxiety disorders:

• Altered physical sensations – palpitations, nausea, dry mouth

• Altered thoughts – irrational thinking, excessive worry

• Altered behaviour – restless, avoidance, an inability to relax or switch off

• Altered emotions – fear, panic.

Anxiety can be the main or ‘primary’ problem or it can be a secondary problem, which means that it is a symptom of another disorder. Depression and substance or alcohol misuse are often associated with high levels of anxiety, but in these cases lasting benefit will come from treating the underlying problem rather than focusing solely on the anxiety symptoms.

In primary anxiety disorders the symptoms tend to have followed a set pattern over several months or years. In these cases the anxiety symptoms occur independently of other mental health problems, however, they can be intensified when coupled with depression and life stress.

There are various types of anxiety disorders such as panic, obsessive compulsive disorder, post traumatic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobias disorder and generalised anxiety disorder.

Panic disorder can strike suddenly with no warning. Symptoms may include a feeling of terror, sweating, chest pain, palpations, fear of heart attack or feeling of ‘going crazy’.

Obsessive compulsive disorder includes thoughts or fears causing constant rituals and routines such constant cleaning and hand washing.

Post-traumatic stress disorder can develop following a traumatic event like a road traffic accident or physical assault resulting in regular flash backs or recall of the event.

Social anxiety disorder can be described as an overwhelming worry and self-consciousness about daily activities and fear of negative judgment or ridicule by others.

Specific phobias disorder includes fear of spiders, heights, flying etc. and often results in avoidance of these situations.

Generalised anxiety disorder involves unrealistic worry and fear with no obvious reason.

Panic attacks are extremely frightening. They may appear to come out of the blue, strike at random and make people feel powerless, that they are losing control and about to die.

A panic attack is really the body’s way of responding to the ‘flight or fight’ response system getting triggered without the presence of an actual external threat or danger. Attacks can occur unexpectedly or can be brought on by a trigger, such as a feared object or situation. When adrenaline floods the body, it can cause a number of different physical and emotional sensations that may affect people during a panic attack. Panic attacks are sudden periods of intense fear that come on quickly and reach their peak within minutes. These may include:

• Very rapid breathing or feeling unable to breathe

• Trembling or shaking

• Palpitations, pounding heartbeat

• Chest pain

• Dizziness, light-headedness or feeling faint

• Sweating

• Ringing in the ears

• Hot or cold flushes

• Fear of losing control

• Fear of dying

Panic disorder is sudden episodes of acute severe anxiety/panic associated with a fear of death or collapse. The key feature of the disorder is the sudden onset, occurring ‘out of the blue’, with no identifiable trigger. It can be accompanied with a persistent concern about future attacks and consequences of the attack (losing control). People with panic disorder often worry about when the next attack will happen and actively try to prevent future attacks by avoiding places, situations, or behaviours they associate with panic attacks.

Worry about panic attacks, and the effort spent trying to avoid attacks, cause significant problems in various areas of the person’s life, including the development of agoraphobia. A phobia is an intense fear of—or aversion to—specific objects or situations. Although it can be realistic to be anxious in some circumstances, the fear people with phobias feel is out of proportion to the actual danger caused by the situation or object.

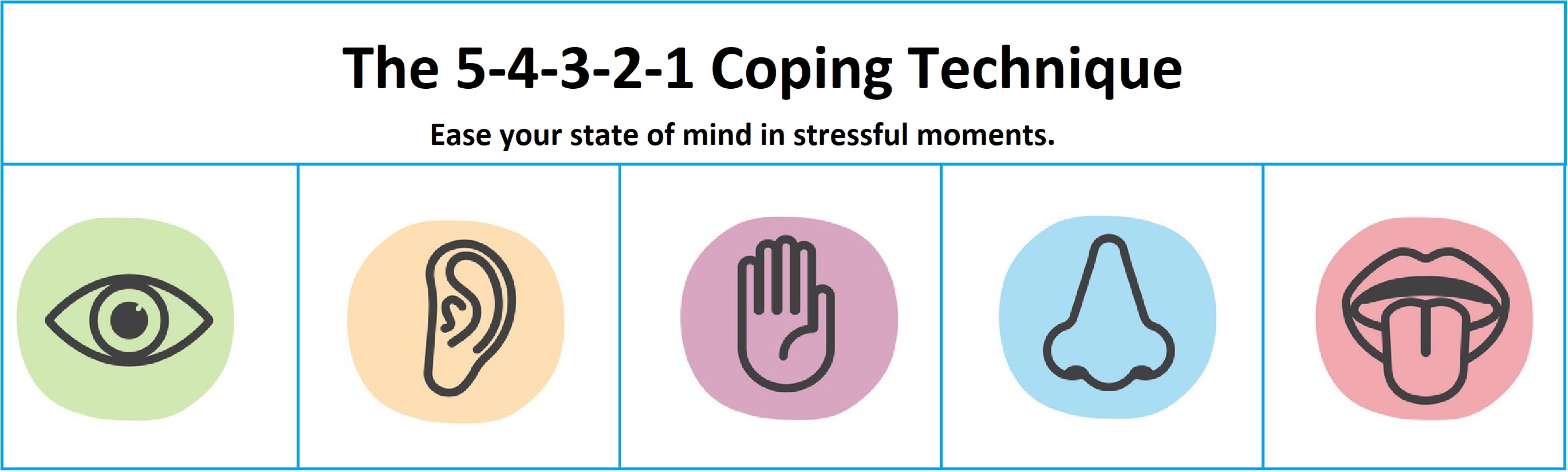

Grounding Exercise using your five senses:

5 things you can see

4 things you can hear

3 things you can feel

2 things you can smell

1 thing you can taste

CBT is a combination of behavioural psychology and cognitive psychology. CBT works on the understanding that our thoughts affect what we do and how we feel, and that it is our thoughts that make us feel bad rather than our life circumstances or situations.

It can be used to treat a variety of conditions, including anxiety disorders. CBT sessions tend to last between 30 and 60 minutes, and can be combined with other supports or treatments. CBT therapists will help you to break your problems down into smaller areas so that you can figure out what the areas of concern are. Part of the work will often include writing down your feelings, thoughts and reactions so you can see patterns and how thoughts and feelings are impacting on your life.

How CBT’s ABC therapy modelling works

The ABC model was created by Dr. Albert Ellis, a psychologist and researcher.

Its name refers to the components of the model. Here’s what each letter stands for:

A. Adversity or activating event.

B. Your beliefs about the event. It involves both obvious and underlying thoughts about situations, yourself, and others.

C. Consequences, which includes your behavioural or emotional response.

It’s assumed that B links A and C. Additionally, B is considered to be the most important component. That’s because CBT focuses on changing beliefs (B) in order to create more positive consequences (C).

When using the ABC model, your therapist helps you explore the connection between B and C. They’ll focus on your behavioural or emotional responses and the automatic beliefs that might be behind them. Your therapist will then help you re-evaluate these beliefs.

Over time, you’ll learn how to recognise other potential beliefs (B) about adverse events (A). This allows opportunity for healthier consequences (C) and helps you move forward.

Take the following scenario. In team meetings a colleague keeps interrupting and speaking over you.

The Activating Event (A) from the ABC model is the interruption

The Beliefs (B) about the event A can lead to rational or irrational thoughts. For example a rational belief may be “that was a bit rude, I’ll be assertive and tell the person I was still speaking and will finish my point”. An irrational belief may be “that was rude, (s)he obviously doesn’t respect me or think I know what I’m talking about and maybe they’re right and I’m not very good at my job.”

The Consequence (C) then may be the emotion we experience. For the rational belief this may be that you feel slightly annoyed by the interruption but you deal with it in the moment and move on from it. With the irrational belief you may question your value and become sad or angry. This type of emotional response will lead to more anxiety.

The ABC model works on challenging the B in response to A and therefore changing the C. So A does not cause C in many cases it is B that causes C. So if we use CBT techniques over time we may develop the skill to challenge our beliefs and this may lead to better outcomes for our mental health and wellbeing and ultimately reduce anxiety levels.

“Positive psychology is the scientific study of what makes life most worth living” (Peterson, 2008).

Positive psychology focuses on the positive events and influences in life, including positive experiences, states and traits. In general, the greatest potential benefit of positive psychology is that it teaches us the power of shifting our perspective.

This is the focus of many techniques, exercises, and even entire programs based on positive psychology because a relatively small change in our perspective can lead to shifts in wellbeing and quality of life

A simple positive psychology exercise to help stay calm in the face of uncertainty:

Martin Seligman, psychologist, offers a quick and straightforward way to refocus the mind.

“The human mind is automatically attracted to the worst possible case, often very inaccurately,” says Martin Seligman, who founded the field of Positive Psychology and suggests “Catastrophising is an evolutionarily adaptive frame of mind, but it is usually unrealistically negative”.

To refocus the mind, Seligman suggests a simple exercise called “Put It in Perspective”, which starts by conjuring the worst-case scenario, which our minds tend to do first, then moves to best-case scenario, and finishes with the most likely scenario. The idea is to redirect your thoughts from irrational to rational.

Step 1: Ask yourself, what is the worst possible situation?

Your partner is usually home from work by 5. It’s 5.30 and they aren’t home. You ring them and get no response. Your anxious mind starts racing. Its 5.45 and you ring them again and it rings out. You think this is totally out of character and they must have been in an accident and if your mind fixates on the worst case scenario you believe you will have a panic attack.

Step 2: Then force yourself to think about the best outcome

In this part of the exercise, you might think, “They noticed we need shopping and stopped on the way home to get that and their phone battery is flat. It’s great that we’ll have the shopping in and have something nice for dinner tonight”.

Step 3: Next, consider what’s most likely to happen

What’s the most realistic explanation in this situation: “My partner does occasionally unexpectedly have to work late and can get caught up in a meeting and may not be able to make a call or send a message. They sometimes don’t realise it’s gotten a bit late and leaving the office 15 minutes late some evenings can lead to being stuck in traffic on the way home.”

Step 4: Finally, develop a plan for the most realistic scenario

This is different than becoming distressed or wasting energy on something that’s unlikely to have occurred. Rather, it’s coming up with a contingency for what could be a challenging thought. If they are not home by 6 can you ring the office? If you can’t get your partner directly, ring reception or a colleague and try and confirm if they are there or have left? If they have been delayed in traffic can you find out if there are delays on their route and estimate how long it might take them to get home. If you notice your anxiety rising can you ground yourself using techniques you can learn. Can you contact a friend to discuss it and get support.

Every person’s anxiety is unique to them and the more individualised the support the better outcomes. There are a wide range of techniques and resources that are available to us all to try and apply to our individual circumstances. If you are suffering with debilitating anxiety please seek support from your GP or consider making contact with a counsellor. The CSEAS is also available to support you and to request an appointment or make an enquiry please contact us:

Tel: 0818 008120

Monday – Thursday: 9am – 5.15pm

Friday: 9am – 5pm

Email: cseas@per.gov.ie

Appointments are available evening and weekends if required. Video conferencing is also available.